Survival in the Gig Economy

Freedom from the nine-to-five or another form of exploitation? The gig economy is both!

Book gives you the truth about about what to expect and helps you make a plan when nothing is predictable.

Freedom from the nine-to-five or another form of exploitation? The gig economy is both!

Book gives you the truth about about what to expect and helps you make a plan when nothing is predictable.

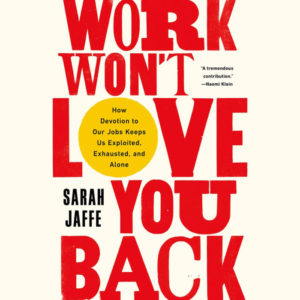

Get if from Goodreads * The Author’s Site * Bold Type Books * Amazon

I read this book not so much because it would contain something new or surprising, but rather to experience an alternative way of describing how our work life has become more dysfunctional. I have spent a lifetime observing, researching, and analyzing the degradation of our work life, so it is always refreshing when someone else notices the same thing and is able to frame it somewhat differently. I realize that my own focus on data and somewhat esoteric economic theories and models will not resonant with everyone. Some folks who are simply fed up may want to hear stories from other folks who are experiencing the same angst without getting bogged down in complicated theory.

The frame that Jaffe suggests is that the way modern work is designed operates to exploit our better natures—that part of us which desires to help others and make the world a better place through what we do for a living. Although some of us may feel “called” to certain work, it too often leaves us exhausted, inferiorized and alone. At the same time, society exhorts us to view what we do as a “labor of love,” to “lean in” and otherwise devote all our attention and energy to work. Which then, of course, keeps us unfocused on the ways that work is exploiting us and unaware of the power relationships that keep us down.

The first part of the book addresses what is often described as “care” work: domestic work (nannies, housekeepers, elder and child care workers), but also includes teachers and persons who work in retail and non-profit organizations. Jaffe describes how much of this work is “gendered,” but we don’t ever really know if the work is devalued because it is primarily performed by women, or vice-versa. Certainly, much of care work has traditionally been performed by women for free, so one might argue that being paid for formerly “free” work is a step up. But, as Jaffe points out, the way care work is structured often juxtaposes the interest of workers against those of their clients. The paid attendant, or caregiver, is expected to be invisible, and “to be made invisible is the first step toward being considered nonhuman.” What has changed is that some women are now able to do more “visible” paid work because others are being paid to do the invisible (i.e., “not work”) work that women used to do for free.

The organization of care work and small micro-tasks through app platforms has made this work atomized, casual and precarious. It has stripped away the personal relationships that might have made such work emotionally (if not financially) rewarding in the past. This also makes it harder for workers to organize—especially if many of them view the “employer” as the folks they care for every day and not the anonymous platform siphoning profit from every transaction. There has been some good news: In 2010, the National Domestic Workers Alliance won the first Domestic Workers Bill of Rights in America. But many of the workers—without a traditional shop floor (where work is discussed) or a break room (where labors laws are legally required to be posted)—are unaware of their legal rights.

In the really old days (up until the Great Depression), 89% of retail establishments were independently owned “mom and pop” stores, where the owners and employees were often the same person(s). No discussion about modern retail work is complete without some mention of the Walmart effect. Throughout the middle twentieth century, Walmart and other “big box” retail stores decimated the network of mom and pops. Jaffe cites one study in Iowa that found 555 groceries, 298 hardware stores, 293 building supply stores, 158 women’s clothing stores, 153 shoe stores, and 116 drugstores had disappeared 10 years after a Walmart moved into the area.

Jaffe notes that “Walmart’s spread across America and the world coincided with—but barely acknowledged—the feminist revolution, even as it relied heavily on the labor of women entering the work force in droves.” As more of these new retail positions came to be filled by women, it institutionalized the view that retail was “not really work,” but something that was done part-time by bored housewives or students who were still being wholly or partially supported by parents. Like child care, housework, and teaching, the tasks performed in these jobs were also deemed “unskilled” and devalued.

Jaffe notes that the biggest challenge in these jobs was not necessarily the specific tasks themselves, but the need for what sociological researchers came to call “emotional labor.” That is, one always had to have a smile and a cheerful demeanor, no matter how rudely the customer (or boss) behaved. Loving the job thus became part of the job itself.

Jaffe next addresses the non-profit-industrial complex. We again start with the history of “charity,” which in the beginning was performed by persons who did not need to work. Charity itself is a relation of power—an ”ethic based on hierarchy and dependency [that] responds only to immediate material needs and relocates collective concerns into a realm of private benevolence.” Here too, we see the gendered structuring of care work applied to wealthy women looking for something to do, and a way to distract from their wealth by “giving back” to those who society had left behind.

Nonprofits whose mission is to organize marginalized groups so they can assert power against the system are faced with the paradox that they are funded by “an inherently unequal capitalist system,” which greatly restricts their ability to change it. Moreover, the emotional blackmail that is applied to all workers is aggravated in the non-profit context, as workers’ passion for social changed is turned into a weapon of exploitation against them. Nonprofit employees are expected to work long and hard hours for little pay, always doing more with less, because they are committed to the organization’s mission. Jaffe describes some of these exploitative practices even in respected organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center, which hired a union-busting law firm when some employees wanted to join the Nonprofit Professional Employees Union.

In the second part of the book, Jaffe looks at occupations where the worker is expected to love the work itself. In the United States, the world of artists and creatives is characterized by a winner-take-all market. The huge (and publicly acclaimed) success of a few superstars never trickles down to the creative community as a whole. It is particularly difficult for artists to survive in the United States unless they come from a wealthy family or have independent sources of funding. Jaffe interviews an artist in Ireland, who received all of her training for free. In Mexico, artists are able to pay their taxes with art work—which is then displayed in public buildings or museums. In the United States, artists “face a series of gatekeepers who remain attached to the idea of art as a meritocracy.” Because the gatekeeps almost invariably come from “more comfortable backgrounds,” working class people are underrepresented in the arts. Creatives are expected to sacrifice material subsistence and stability in the pursuit of work that is “meaningful.”

Jaffe next looks at internships. In the past, this was a way for workers to learn a job before being offered a job. Here again, we see the gendered nature of how internships are structured; In fields dominated by men (like engineering), internships are paid and protected by labor law. In fields dominated by women (nursing, education and social work), the interns are unpaid and not classified as “employees.” Colleges and universities in particular have jumped on the unpaid-internship-in-exchange-for-academic-credit bandwagon. Jaffe cites data indicating that between 50% and 75% of four-year college students do at least one internship. Jaffe again points out that “internships are extremely gendered…insofar as they demand meekness, complicity, ceaseless demonstrations of gratefulness, and work for free or for very little pay, put workers in a feminized position, which, historically, has been one of disadvantage.”

Next, Jaffe turns to academia, quoting professor Stanley Aronowitz, who once called academia “the last good job in America.” But, just as internships are a form of “hope” labor (the hope is that it will lead to a paying job), the trend toward converting tenured faculty positions into adjuncts also creates an army of “hope” workers—highly educated persons living on the edge of precarity in the “hope” of earning a coveted tenured position. In the UK, former PM Margaret Thatcher eliminated tenure in 1988. In the US, tenured positions are being eliminated both through the corporatization of education and the globalization of the academic labor “market.” Those coming into the system are thus kept on a constant treadmill of “production,” in the expectation that once they have paid their dues, they will finally enjoy respect and the good life that goes with it. The odds, however, are definitely not in their favor.

In academia, we again see gendered work structures, with faculty who are women or BIPOC often doing the “invisible work of making the university a better place” by serving on diversity committees or mentoring students. The students themselves are more stressed and anxious, which negatively impacts their learning and willingness to take risks. Some academics make their escape by “jumping ship” and going into “direct service to capital,” where they become analysts for Wall Street or elite think tanks. Others find meaning and dignity by working to change the system within through their union or other faculty organization.

The last two occupations Jaffe looks at are workers in the technology and sports industries. Although these folks are better paid than workers in more “feminized” occupations, they too are subject to the workaholic exploitation grounded in the expectation of eventually striking it “rich” and the myth of individual meritocracy (which serves to thwart the development of solidarity). Moreover, although these folks may seem highly paid to most of us, Jaffe argues that we need to view their salaries in comparison to the immense fortunes of tech oligarchs and the professional sports industrial complex.

In the end, Jaffe argues that we need to develop a “politics of time.” Work should do more than provide for our material needs (which it often fails to do for many of us), but should also strengthen our personal relationships and enhance our communal public life. Rather, “…our personal relationships are to be squeezed in around the edges, fitted into busy schedules, or sacrificed entirely to the demands of the workplace….The shreds of the neoliberal work ethic have turned our hearts into appointment books.” Perhaps it would not be a bad thing to love our work…but our work should be doing more for both us and our communities than creating obscene fortunes for a few while exhausting and alienating the rest of us.

The one thing I would have liked this book to address is the psychological effect of continuous cognitive dissonance on our mental functioning. That is, what happens to how we think when we are required to spout how “happy” we are and how “great” everything is while we are overworked, underpaid, and our emotions are exploited with false hope. Perhaps there are studies out there somewhere….

I recommend this book as a companion to The Great Jobs Deception. We all need to be talking about what is happening to our work life.