Survival in the Gig Economy

Freedom from the nine-to-five or another form of exploitation? The gig economy is both!

Book gives you the truth about about what to expect and helps you make a plan when nothing is predictable.

Freedom from the nine-to-five or another form of exploitation? The gig economy is both!

Book gives you the truth about about what to expect and helps you make a plan when nothing is predictable.

Get it from Thriftbooks * Goodreads * Amazon

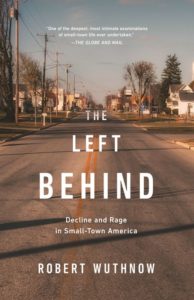

Robert Wuthnow was born and raised in Kansas, so he is no stranger to the culture in America’s rural heartland. After completing his undergraduate studies in Kansas, Wuthnow earned his Ph.D. in sociology at the University of California in Berkeley, where his dissertation focused on the consciousness and social changes of the so-called “counter-revolution.” Wuthnow is currently a professor of social sciences at Princeton University, where his research (and many books) have focused on the intersection of rural life and religion: Remaking the Heartland (2011); Red State Religion: Faith and Politics in America’s Heartland (2012); Rough Country: How Texas Became America’s Most Powerful Bible Belt State (2014).

In The Left Behind, Wuthnow returned to his small-town roots to help understand not just Trumpism, but the rage behind the politics of grievance and resentment. Was it a matter of economics, where small towns have been left behind economically while the suburbs and (some) urban areas have boomed? Or was it cultural—cities were considered progressive and “diverse,” while small towns were considered “backward” because of their Whiteness and religiosity? There is plenty of evidence that small towns and rural areas have been losing both population and economic resiliency for decades. But Wuthnow suggests there is something deeper. Although Wuthnow never proposes a definitive answer, he does suggest something which I can sympathize with.

In the middle 90s, my husband and I lived in rural NW Arizona. As a licensed professional, I was required to keep up a certain level of continuing education (CE) credits. In the days before the Internet was everywhere, nearly all of these classes were offered in either Phoenix (the state capital) or Tucson, the two largest cities located in the SE section of the state. But there was more than an added inconvenience—those of us who lived in these poorer areas (called “out counties” by the wealthier urbanites) had to travel more than 200 miles one way to do our CE rather than a drive across town—but also had to contend with subtle forms of inferiorization. There was a sense that we weren’t as smart or as sophisticated as our counterparts in the urban areas—even though we possessed the same level of education and experience. My sister, who is a professor at a small state university in Western Minnesota encounters a similar attitude from her peers in the “cities” (Minneapolis-St. Paul). We see a similar complaint about lack of respect and failure to understand their challenges that percolates beneath the rage expressed by Wuthnow’s interviewees.

Wuthnow and his research assistants conducted over a thousand in-depth interviews while visiting people in the places they call home: the farms, factories, town halls and homes where people live and make their livelihoods. While visiting hundreds of small town communities, Wuthnow also learned about their histories—both from the oral interviews and written historical records. As Wuthnow found, the lives of rural residents are “complex” and not so easily defined by a one-size-fits-all explanation. However, one thing that seemed apparent is that rural and small-town residents are more connected with a sense of place than their urban counterparts.

Wuthnow characterizes small town life as viewing oneself as a member of a moral community. This is not necessarily a form of “morality” in the sense of good and evil, but rather a sense of connection to place and mutual obligations to others in the community, as well as a responsibility to uphold and maintain the community’s way of life. Here, Wuthnow portrays the “community” part as being a virtue. Even in a town with a population of a few thousand, it is not likely that everyone personally “knows” everyone else; rather the expectation is that you should know everyone. Therefore, friendly nods and greetings are offered to all, because even if you don’t know someone’s name, you probably have seen him or her somewhere around town.

In addition to everyday friendliness, people generally are willing to help a neighbor in need (without judgment as to deserts). Wuthnow found that “residents of small towns or rural areas were significantly more likely than residents of cities or suburbs to feel they could count on their neighbors if someone in their family became seriously ill.” There is also a sense of civic responsibility and mutual reciprocities. Almost everyone belongs to at least one civic-oriented group like Lions, Kiwanis, Rotary clubs, or volunteers at church or charitable activities (Meals on Wheels, March of Dimes), and other organizations that serve the needy and vulnerable in the community. Indeed, most of these folks would score high on prosociality. The culture of volunteering reinforces both a sense of community as well as a self-sufficient ethos that, “we can take care of our own and each other.”

The downside is that this sense of community also maintains a “boundedness” that separates insiders from outsiders. When right and wrong, good and bad are defined by the community, outsiders can present a threat to the collective norms and practices that define the community. This existential threat can come not only from “city-slickers” moving into town or immigrants brought in to work for low wages, but also from legislation and policies dictated from state capitals and “Washington.” At the same time, there seems to be a grudging recognition that the towns are going to have to change if they hope to survive.

Small towns have born the brunt of the economic changes that have been happening everywhere: small businesses forced to close when corporate chains move into the area, plants closing and loss of jobs. These events are more devastating to small towns, who don’t have larger and more diversified economies to absorb them. When jobs leave, young people move away to the cities in search of employment. Young people who go away to college often do not return, creating a form of “brain drain.” Family farms are swallowed up by huge corporate agribusinesses, and farmers are forced to “get big or get out.”

The family farm is no longer enough to support the next generation if you have to split it among offspring. The agribusiness that replaces family farms then brings in immigrants (usually Latinos) to work on the land because they can be hired cheaply. Other importers of immigrant labor are large centralized meat and poultry processing facilities. Companies like IBP (Iowa Beef Processors) and Tyson favor right-to-work states in the South and the heartland for these huge processing plants, where they can pay immigrant labor “dirt cheap wages.” The residents thus see immigrants or “outsiders” doing the work that used to be done (on a smaller scale) by families on their own farms, aggravating the impression that immigrants are “taking jobs” away from residents.

Wuthnow describes the strategies that rural and small town communities deploy to address problems such as loss of jobs and population as “makeshift solutions.” Where in previous times, the community itself generated sufficient income to support its own civic projects, now such things require new skill sets to bring money in from elsewhere—lobbying and grantwriting skills—which locals usually don’t have because all the college graduates have moved away. Alternatively, someone hires an “economic development” consultant, whose technocratic orientation is at odds with local culture. In one town Wuthnow visited, a long-term manufacturing plant had closed, so many residents were either underemployed, working part-time jobs, or commuting over 30 miles one way to jobs in the city. The town manager told Wuthnow, “We have a lot of screamers. What they’re yelling about may be completely unreasonable, but they have a need to vent…once you blow through all the smoke, a lot of times it’s a problem that isn’t possible to address at this level.”

The locals, however, aren’t completely ignorant about the larger issues affecting them. Most farmers, for instance, agree that climate change is happening and that it is caused by human activity—especially since they see the effects on their own farms. They also were not anti-regulation in an absolutist sense—believing that such was necessary to keep food pure, restrict genetic engineering, and control the importation of cheap foreign commodities. However, they also grouse at regulations that are more appropriately aimed at huge agribusiness, claiming the regulations (which the big boys can hire attorneys and lobbyists to get around) only make it that much harder for the small farmer to compete.

In the chapter on bigotry, Wuthnow suggests that what some of us might perceive as racism might be confounded with more generalized angst about change and loss of community. Racism and bigotry do exist, and complaints about “newcomers” often are couched in terms of crime, drugs, violence and “riff-raff,” or anyone (this can include white people) who does not work to support themselves. But suspicion of outsiders is sometimes directed at white people as well: some of the folks who lived in these communities for less than two decades reported that they still didn’t feel like they quite belonged, especially when many of their neighbors had roots in the area going back generations.

Wuthnow recognized that rural and small town grievance seemed to be deeper (and more intense) than the loss of jobs, the moving away of young people, and newcomers who looked different. He probed the specifics of grievances against government. Like taxpayers everywhere, there was a feeling that taxes were too high. But the complaints also were directed at corporations, who weren’t paying their fair share, receiving tax breaks at the expense of small communities. Other tax-related grievances revolved around urban renewal and housing projects, while there was no money to take care of the local infrastructure projects.

Grievances against “Washington” alternated from complaints about “unconstitutional” usurpation of local control, along with its cultural and geographic distance. “Washington” didn’t understand the lives and culture of people living in small-town America. This was especially acute in matters of religion: the government should not be forbidding prayer in schools and at the opening of public events when this is what the community wanted. Religion “is part of the moral warp and woof of where they live…[and] plays an important role in holding the community together.” Complaints against Washington thus ranged from “They’re just not listening to us out here” to “bureaucracy is inimical to good government,” to “Washington lacks common sense,” to “Leave us alone.” Although politically most people were conservative, complaints about Washington “being broken” and corrupt usually had blame enough for both parties.

Unfortunately, Wuthnow does not ask his interviewees where they get their news and information about what is going on the larger world. Many of the adverse effects (loss of jobs, concentration of industries) experienced by these folks are as much the result of actions by global elites and the corporatocracy as they are specifically from actions of “government.” On some level, the people seem to sense this, but the finger tends to either point at a distant and aloof “Washington” or locally at immigrant scapegoats. Most of the grievance could be reduced to a simplistic “big government is bad” explanation, because it takes power away from the community. But the economic power was already being sucked away, and while “Washington” may have overseen this, it was mainly being driven by the oligarchs who run things (and who we don’t vote for).

Wuthnow also doesn’t have any prescription for finding common ground with these folks. It is admirable that, as a “liberal” academic type (who many of these folks do not trust in the abstract), he was able to earn their trust and hear their stories. Listening is probably a good place to start, but it seems like one side is always the one to be doing the reaching out. Liberal academic sociologists like Wuthnow and Arlie Hochschild (Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right) venture into territories where they are likely to be unwelcome, as they attempt to understand and identify points of sympathy. Yet, there doesn’t seem to be a corresponding effort on the part of the townsfolk to understand the “strangers” and immigrants in their own midst, or even why these “outsiders” have chosen to live there. Moreover, what will help these people see that the destruction of their communities is being driven by forces even larger (and less visible) than the government in Washington?

If there is one grievance that might be the basis of common understanding, it is the sense that the “powers that be” do not know what your life is about and moreover, do not care about it. Frankly, this is a fairly universal grievance that is also shared by many people in urban areas as well. This segues into the experience of inferiorization. The power elites and technocratic experts think they know what is best for us—without making an effort to hear from us. This is not something that is unique to folks living in small towns, but to anyone who occupies a position lower in the socio-economic hierarchy. The complaint that “they” think they’re better than “us” goes both ways.