Survival in the Gig Economy

Freedom from the nine-to-five or another form of exploitation? The gig economy is both!

Book gives you the truth about about what to expect and helps you make a plan when nothing is predictable.

Freedom from the nine-to-five or another form of exploitation? The gig economy is both!

Book gives you the truth about about what to expect and helps you make a plan when nothing is predictable.

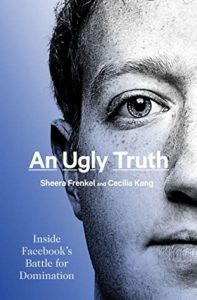

Sheera Frenkel and Cecilia King spent over 1,000 hours interviewing more than 400 current and former Facebook employees, executives and investors to give as an “insider view” of a company that played a prominent role in some of the major events of the past few years. The authors were able to gain access to never-reported emails, memos and white papers approved (or involving) top executives. Facts were confirmed via multiple eyewitnesses and corroborating documentation. The authors point out that their interviewees “put their careers at risk” in order for the full truth to come out. Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg refused requests for interviews.

One comes away from An Ugly Truth with the clear sense that Facebook has too much power. A single company—especially one that is dominated by a single fallible individual—should not be in a position to dictate policy involving fundamental rights such as free speech and privacy. Yet the book is not entirely about Facebook bashing, or even Zuckerberg bashing. At times, the company seemed to take its responsibilities seriously. It was also instrumental in uncovering Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election. The authors describe difficult debates among staff about whether or not Trump (or other inflammatory political comments) violated the platform’s rules that barred hate speech, where the line was with respect to the First Amendment, and concern about the perception of “liberal bias.” The folks at Facebook were primarily tech geeks and marketing gurus, who were unlikely equipped to address the socio-political issues created by the shear reach of the platform.

Zuckerberg himself is portrayed more as a gung-ho techie workaholic rather than the evil greedhead persona that is typically associated with monopolies. There are stories of Zuckerberg running all-night coding sessions fueled by Red Bull and Cheetos. However, he did possess the drive for domination, even if its intent was basically benevolent. Zuckerberg preached the gospel of universal connection, and he intended that Facebook be the one to accomplish this.

Russian Election Interference

The main hero in this story is Alex Stamos. Stamos had previously worked as an information security officer at Yahoo. He was one of the youngest and most high-profile cybersecurity experts in Silicon Valley. Another hero is Ned Moran, a cybersecurity professional with expertise in foreign-backed hackers who reported to Stamos. Moran knew that the DCLeaks page was a Russian asset, and he had been monitoring it. Moran was able to trace Facebook ads back to the St. Petersburg-based Internet Research Agency, which had spent about $1,000 on some 3,300 advertisements. IRA operatives had identified so-called “seam issues,” or highly divisive issues around race, gun control and immigrants, which they then used to set up some 120 pages that promoted extreme viewpoints. Although most of the pages purported to support Trump, some of the fake pages were also promoting Bernie Sanders. Facebook also found that the IRA had been able to organize offline “real world” events, and had even contacted Facebook employees for information about how to better run their sites.

When Stamos arrived at Facebook, he was already concerned that the company wasn’t doing enough to protect users’ privacy and security. “Facebook had no playbook for the Russian hackers, no policies for what to do if a rogue account spread stolen emails across the platform to influence news coverage.” Stamos became increasingly worried following Trump’s “Russia, if your listening” statement on July 27, 2020. Other Facebook employees shared Stamos’ feelings of impending dread.

Throughout 2016, misinformation was spreading like wildfire on Facebook, and employees were posting concerns in work groups about what to do. According to unidentified sources, some Facebook lawyers had passed the threat teams intel to the FBI, but they never heard anything. Stamos was in Germany—ironically speaking to European officials about the threat of social media influence on elections—when he realized Zuckerberg had never been briefed about the Russian hacking. On December 9, 2016, Stamos called a meeting with Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg.

Although Stamos and his team had uncovered information that even the U.S. government did not have, their efforts were not appreciated because it forced Facebook executives to “look at problems they would rather not address.” Facebook executives were more worried about what they would say to the public. But Zuckerberg and Sandberg did give Stamos the authority to “get to the root” of the Russian election interference. To address the threat, Stamos recommended that Facebook reorganize its security team. Which Facebook did do, but Stamos found that his team had been broken up and his own duties rendered ambiguous.

In response to its findings of Russian hacking, Facebook instituted a policy of prohibiting accounts it determined were involved in “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” Facebook removed over 3,000 ads and the accounts associated with them that had violated its policies. On September 7, 2017, Stamos presented his findings to the Facebook board and told them it was likely that there was more Russian activity on Facebook that his team had not been able to uncover. One board member asked, “How the f*ck are we only hearing about this now?” Stamos also shared the results of his investigation with Virginia Senator Mark Warner, who was then Chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee. Based on Facebook’s data, the Committee concluded that some 126 million Americans had been exposed to IRA content.

The Facebook security team felt like they were under attack from Congress: They had exposed a Russian disinformation campaign that the U.S. government itself had completely missed, yet now they were being vilified for taking so long to make their findings public. While many on the security teams were demoralized at the lack of action from both the company and the government, there was some sense of vindication when Robert Mueller announced indictments and guilty pleas for election interference crimes. Stamos quietly and amicably resigned from Facebook shortly thereafter.

Privacy

Zuckerberg was driven by numbers indicating engagement—not just more users, but users spending more time on the platform. Facebook had developed an algorithm to produce a News Feed that drew from posts, photos, and updates that users had already entered into their Facebook profiles. The News Feed was “sprung” on Facebook users without any notice or provision to opt out. Within 48 hours, 7% of Facebook users had joined an “anti-News Feed.” Investors were panicking, and several of them asked Zuckerberg to disable the News Feed. But the numbers looked good to Zuckerberg—people were spending more time on the site. In response to the ascendence of Twitter in 2009, Zuckerberg made more changes to Facebook’s privacy settings, which one privacy advocate characterized as deception bordering on illegal fraud. In 2011, Facebook found itself subject to an FTC investigation and Congressional inquiries, which resulted in a settlement that required the company to undergo regular privacy audits for the next twenty years.

The next public crisis for Facebook came with the news that Cambridge Analytica, a company based in the UK, had harvested vast amounts of users’ data from Facebook accounts without their permission. The source of the Cambridge Analytica leak was traced to the introduction of Open Graph, a program that allowed outside app developers to gain access to user information. Open Graph allowed Facebook sales reps to offer enticements to expand partnerships (and Facebook traffic) with other developers. Although at least one Facebook employee tried to warn about privacy issues with the program, these concerns were minimized, and the employee left the company. Zuckerberg shut down Open Graph in 2014, but not before an academic at Cambridge University named Aleksandr Kogan tapped into it and began harvesting data. Kogan had turned information from 90 million Facebook users over to Cambridge Analytica, in violation of Facebook rules for app developers.

Cambridge Analytica itself was a company apparently run by Trump advisor Steve Bannon and funded by the wealthy Mercer family. [The full story of Cambridge Analytica is told in Mindf*ck] The FTC announced an investigation into whether Facebook had violated the 2011 consent decree, and Facebook stock dropped 10 percent. Zuckerberg again appeared before a Congressional inquiry “looking pale and haggard.” He attempted to deflect judgment by pointing out how Facebook had helped the MeToo movement and raise money for Hurricane Harvey victims. In March of 2018, Facebook began its own internal investigation of Cambridge Analytica, although this investigation focused mainly on the technical logistics of data transfer.

Sources for An Ugly Truth report that Sheryl Sandberg was deeply troubled by Facebook’s slow fall from favorable public opinion even before the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke. A Factual Democracy Project survey conducted in March 2018 found that Zuckerberg had a 24% favorability rating. Sandberg felt like she had to constantly defend attacks on the intentions of company executives. Although both Sandberg and Zuckerberg admitted that the company had “made mistakes” and “needed to do better,” their intentions had always been prosocial. Some Facebook executives suggested that the intensity of public backlash was due to the fact that Cambridge Analytica was associated with Trump’s election, which was “why everyone is mad at us.”

Zuckerberg’s “solution” to the privacy issue was the creation of private groups. By now, Facebook had acquired WhatsApp and Instagram. It then linked and encrypted these platforms into its own Facebook Messenger. Some employees pointed out that these changes weakened Facebook’s ability to monitor content. Although Zuckerberg heard out employee objections (he was always open to hearing everyone out and then doing his own thing at the end of the day), he went forward with the private groups. By merging the messaging services back-end technologies, Facebook could drive more traffic between the apps and collect more information about users. It also violated promises Zuckerberg had made to both government officials and the founders of WhatsApp and Instagram to keep the apps independent.

AI Feeds Disinformation

Public concern generally centered on the effect of misinformation itself. At Facebook, executives were more concerned about the company being blamed. As online invective grew and became increasingly disconnected from reality, News Feed employees raised the issue with Facebook managers, only to be told that fake news did not expressly violate Facebook’s rules. Although Facebook did have rules against content that promoted violence, there is often a fine line between what is merely words (protected speech) and what eventually can (or does) lead to actual harm.

Zuckerberg shared the Silicon Valley cultural ethos that all information should be free. It was not Facebook’s job to censor. Zuckerberg—who is Jewish—even refused to take down false content that denied the Holocaust (as well as the shooting at Sandy Hook). Zuckerberg “viewed speech as he did code, math and language. In his mind, the fact patterns were reliable and efficient, and he wanted clear rules that one day could be followed and maintained by artificial intelligence systems.” He assumed that the truth would somehow prevail in the free marketplace of ideas—that users would flag “fake news” stories, which would alert the algorithms to make them harder to find. Zuckerberg had the same type of logic with respect to “clickbait,” presuming that even if users would click on a story, they would spend less time on it, and the story would be pushed down the queue in the News Feed. The fallacy of this is that clickbait sites countered by tweaking their headlines to avoid being downranked.

What Zuckerberg failed to understand was how Facebook’s algorithms were designed to favor sensationalism. Moreover, the algorithms could measure in microseconds the amount of time that a user spent on a specific site of article. When the algorithm had “figured out” that a user was more likely to spend time on certain content, this is what made it to the top of that user’s feeds. New psychological theories arose to explain a phenomenon called “emotional contagion.” Facebook engineers complained about false “clickbait” stories going viral and that the algorithms were feeding users the equivalent of addictive “junk food.”

According to the authors, Facebook was “well aware of the platform’s ability to manipulate people’s emotions, as the rest of the world learned in early June 2014, when news of an experiment the company had secretly conducted was made public. The experiment laid bare both Facebook’s power to reach deep into the psyche of its users and its willingness to test the boundaries of that power without user’s knowledge.”

A series of experiments by Facebook data scientists divided content that was categorized as “good for the world” or “bad for the world.” What the experiments found was that content that was “good for the world” reduced time spent on Facebook, while content that was “bad for the world” did the opposite. Since the holy grail at Facebook was time spent on the platform, all of the new changes to protect privacy were “moderated” to avoid reductions in engagement. As one Facebook data scientist observed, “The bottom line was that we couldn’t hurt our bottom line.”

Disinformation Turns Deadly

Although Facebook had no rules against disinformation in general, it did have rules against foreign election interference as well as hate speech, or content that was intended to promote violence. As early as 2014, a group of academics researching hate speech had contacted Facebook engineers about how Facebook had been hosting “dangerous” and “dehumanizing” Islamophobia. Facebook employee’s angst with hateful disinformation reached a peak when Burmese soldiers in Myanmar posted “genocide in real time” documenting the slaughter of Rohingya Muslims.

Apparently, someone had posted false reports (with manipulated images) that Muslims had raped a young Buddhist woman. Riots had broken out in Myanmar following these false reports, and even NGOs sent warnings to Facebook. People were getting killed and there was no response. On the third day of rioting, the Burmese government shut down Facebook for the whole country. An activist on the ground reported frustration dealing with Facebook’s “Kafkaesque” response, and the fact that there was only one Burmese-speaking rep (located in Dublin) assigned to monitor all the content in the country.

Matthew Smith, the CEO of a human rights organization in Southeast Asia, requested Facebook to help him identify Burmese soldiers who had participated in Rohingya massacres. Smith knew that Facebook kept a record of everything its users posted on the platform, including accounts that had been removed. Smith was hoping to build a case against the perpetrators to take to the International Criminal Court at The Hague. But Facebook refused his request, claiming that release of this information would be a violation of its privacy terms. Facebook was concerned that the Burmese soldiers could sue it. They also said there was no internal process to find the harmful content Smith was requesting. The authors state that this was misleading because Facebook had worked for years with law enforcement to build cases against child predators. According to Smith, “Facebook had the chance to do the right thing again and again, but they didn’t. Not in Myanmar. It was a decision, and they chose not to help.”

Too Much Power

A major problem with Facebook is that it essentially operates as a monopoly. By 2019, Facebook had acquired nearly 70 companies and received some 80 percent of the world’s social networking revenue. When the FTC fined Facebook $5 billion for the Cambridge Analytica breach, this represented only some 3.5% of revenues. Until then, the biggest data privacy fine against a tech company was a $22 million fine against Google in 2012. Apparently, privacy fines are a mere cost of doing business for tech monopolies.

With monopoly power comes political power—or enhanced power that derives from access and influence. We learn that Zuckerberg had at least two meetings with Trump at the White House that were not on the official White House schedule and could not be confirmed by the presidential press pool. The first meeting occurred on the afternoon of September 19, 2019. Trump—who had tens of millions of followers on Facebook and had effectively used the platform for his own advantage—had accused Facebook of censoring his followers and had made statements that the company was too big. According to the authors, Zuckerberg was worried about the potential break-up of his company.

Zuckerberg had another secret dinner meeting with Trump. This time, he was joined by his wife, Dr. Priscilla Chan (a former pediatrician), along with Melania, Ivanka and Jared Kushner. He was there to tout Libra—his new project involving blockchain (crypto) currency. Throughout the turmoil of the 2020 election and Facebook’s ongoing moral dilemmas, Facebook’s $55 billion in cash reserves gave it endless options to buy or innovate its way into new lines of business. Facebook had already purchased Kustomer—a corporate communications software company—for $1 billion.

Facebook’s immense global reach and connections in China made through the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (a philanthropic foundation Zuckerberg and Priscilla had set up in 2015) gave Facebook advance information into the early stages of the Covid pandemic. While the Chinese government and Trump were downplaying the virus, Zuckerberg ordered his department heads to “drop all nonessential work and prepare.” The civic engagement team, which had set up a centralized hub for sharing voting information, shifted to setting up a hub for information from the CDC and World Health Organization. Facebook geared up with a plan to remove misinformation about the new virus—a shift from its policy that “fake news” would not be removed. It was also one of the first U.S. companies to shut down and set employees up to work from home. “Positive headlines about the company’s response provided a boost to employee morale…One month into the pandemic, Zuckerberg was sent data that revealed that the PR blitz was making a difference to Facebook’s public image.” While Facebook is to be commended for taking action in the early stages of the pandemic that our own government was unwilling or unable to do, it is problematic when citizens have to rely on the good will of an unaccountable private company to protect public health.

Appeasing the Radical Right

In late 2016, sites promoting false information and conspiracy theories were regularly among the top ten most viewed sites. Facebook employees were demoralized and concerned about the company’s facilitation of spreading false information. One employee posted a question about what Facebook’s responsibility was to “prevent a Trump presidency.” Although the PR staff advised Zuckerberg not to answer the question, Zuckerberg answered it by reiterating his commitment to free speech. However, the fact that the question was asked was leaked to the media and pounced on by Fox News and right wing blogs. From here on, some of Facebook’s energies and efforts were spent countering charges of bias—which often resulted in failure to enforce the company’s policies against disinformation and hate speech.

When right wing charges of bias against Facebook came out, Sheryl Sandberg—who was arguably more politically savvy than Zuckerberg and tended to be in charge of relationships with Congress—stepped aside. Sandberg had connections to prominent Democrats (including Hillary Clinton) and had recently lost her second husband. So she arranged a meeting between Zuckerberg and right wing media personalities. The meeting was joined by Peter Thiel—the founder of PayPal and member of Silicon Valley’s masters-of-the-universe who also sat on Facebook’s board—AND was also a Trump supporter. “The meeting was a turning point for Facebook, which until then had pledged political neutrality. And it marked a pivotal moment for Sandberg, whose decisions would increasingly become dictated by fears that a conservative backlash would harm the company’s reputation and invite greater government scrutiny.”

Trump had always had a grudge against Silicon Valley for its support of Hillary Clinton in 2016. Zuckerberg had always taken a public position of political neutrality because it was good for “business.” For obviously practical reasons, Facebook’s top lobbyist had been building relationships with influential conservatives, including Lindsey Graham and Tucker Carlson, during the Trump administration. Facebook was constantly walking the line between attempting to mollify conservative critics while touting its efforts to prevent foreign election interference to Democrats. Meanwhile, the Trump campaign was planning to spend at least $100 million on Facebook ads—more than twice what it spent in 2016—intended to “overwhelm voters.”

Facebook’s Non-Censorship Ethos Collides with the 2020 Election and January 6th

As the 2020 election loomed, Facebook was issuing press releases confirming its prior position that political ads would not be fact-checked. Zuckerberg had given Trump’s account “special dispensation” against enforcement of Facebook’s rules because he was an elected official. Trump was also the single largest political advertiser on Facebook. However, Trump continued to put Facebook to the test, and we see Sandberg scrambling to do damage control. A former CIA officer was hired to develop a system to locate and review any political ad on Facebook that could operate to disenfranchise voters. Yaёl Eisenstat presented her idea as a “win-win” that would protect both the company and voters, but her proposal was met with a combination of indifference and hostility. Eisenstat left the company after only 6 months.

Throughout 2020, massive amounts of disinformation were spread on Facebook. Much of the disinformation involved the coronavirus pandemic as well as election disinformation, threatening both public health and democratic institutions. In May of 2020, Facebook created an Oversight Board—an independent panel comprised of academics, former political leaders and civil rights leaders—to adjudicate freedom of expression cases. Although the Board was empowered to make decisions without Zuckerberg’s approval, it was fraught with conflict, as members argued why the platform didn’t treat all autocrats across the globe equally, or why the insurrection at the U.S. Capital was any worse than the violence in Myanmar. “Yet again, the company had figured out a way to abdicate responsibility, under the guise of doing what was best for the world.”

At one point, Trump called Zuckerberg, wanting to ensure that his Facebook account was safe. Zuckerberg attempted to explain to Trump that statements like, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts” were divisive and inflammatory. Whoever was also there on the call reports, “Zuckerberg mainly listened while Trump did his usual talking in circles.” The reporter also states that while Trump never apologized, he “did the bare minimum so that Facebook wouldn’t remove it.”

Not only was disinformation mushrooming on Facebook, so was hate speech. And this time, most of it was not coming from Russia, but an array of domestic websites and media companies. We see Zuckerberg alternating between his home in Palo Alto and his ocean-side ranch in Hawaii, as he observes growing protests while Trump “ramped up his efforts to discredit the legitimacy of mail-in ballots” prior to the 2020 election. According to the authors, the most extreme behavior was taking part in the closed private groups.

On July 7th, a group of Facebook critics called Stop Hate for Profit met on a videoconference call with Zuckerberg and his top executives. Zuckerberg defended Facebook, stating that the platform’s AI was now able to detect 90% of harmful hate speech, “a huge improvement.” But the 10% that went undetected represented millions of posts filled with hate speech. Zuckerberg was accused of not enforcing his own policies because “you have an incentive structure rooted in keeping Trump not mad and avoiding regulation.” At the same time, Zuckerberg’s own data were showing a disturbing increase in Holocaust denialism and conspiracy theories.

In late summer, Zuckerberg ordered his policy team to begin crafting a policy to ban Holocaust deniers. One employee stated that Zuckerberg was explaining his reversal in terms of “evolution.” In October 2020, Facebook announced a policy against Holocaust misinformation, and it also banned QAnon. Facebook was quietly removing thousands of militia groups and “pivoting away from long-held beliefs on free speech, but no one at Facebook… articulated it as a coherent change in policy…Both Zuckerberg and Facebooks PR department framed the action as individual decisions that happened to come at the same time.” To its credit, Facebook was the fastest to remove problem content, but “Facebook employees felt like they were fighting against an impossible tide of misinformation.”

On the morning of January 6, 2021, Facebook’s security teams became increasingly alarmed when user complaints of violent content jumped tenfold. “As Zuckerberg and his executives debated what to do, a chorus was growing across different Tribe boards—engineers, product managers, designers and members of the policy team all calling for Facebook to ban Trump from the platform, once and for all….By mid-afternoon Wednesday, as the last of the rioters was being escorted away from the Capitol, Zuckerberg had made up his mind to remove two of Trump’s posts and to ban the president from posting for twenty-four hours.” The ban was later extended through the inauguration, and then “indefinitely.”

After the insurrection on January 6th, prosecutors revealed how militia groups like the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys had openly discussed their plans on Facebook, including plans to carry weapons into Washington and the violence they were expecting (and hoping for). Although Facebook finally took action, it was too little to late, and the company continues to absolve itself. In a January 11th interview with reporters, Sandberg had been prepped with Facebook talking points. Sandberg deflected the blame for January 6th on new social media companies that catered to the far right.

Throughout Facebook’s seventeen-year history, the social network’s massive gains have repeatedly come at the expense of consumer privacy and safety and the integrity of democratic systems. And yet, that’s never gotten in the way of its success….The algorithm that serves as Facebook’s beating heart is too powerful and too lucrative. And the platform is built upon a fundamental, possibly irreconcilable dichotomy: its purported mission to advance society by connecting people while also profiting off them. It is Facebook’s dilemma and its ugly truth.

One comes away from An Ugly Truth with the impression that Zuckerberg and Sandberg are not villains. Rather, they are flawed human beings who created something that grew beyond their ability to control it. Although Zuckerberg was hell bent on domination of the social media space, he was not motivated primarily by greed. He seemed to operate from an ethos of unfettered free speech and maximum connection—which in certain contexts are laudable, prosocial objectives. His algorithms didn’t calculate the dark side of human nature.

The Silicon Valley masters-of-the-universe want to impose an AI-controlled utopia (dystopia) on the rest of us. They believe that AI is able to make decisions that are uninfluenced by human fallibilities. How does AI identify fake news? Hate? Should one company—especially one that is primarily influenced by one individual—be making decisions about fundamental human rights such as speech and privacy. Another important issue that is implicated is the influence of money in popular discourse generally and politics specifically. Should the reward of profit be tied to the amplification of communication that is poisonous to the public psyche? These are questions that we—collectively as a society, and not Facebook—should be answering. And this discussion should happen somewhere that is not being monitored and controlled by a single entity. Americans should not abide by the concentration of such power.